Over the years, I have compiled a list of music called “music that makes me cry”. On the top of the list is Glenn Gould’s arrangement of the Prelude to Act 1 of Meistersinger by Wagner.

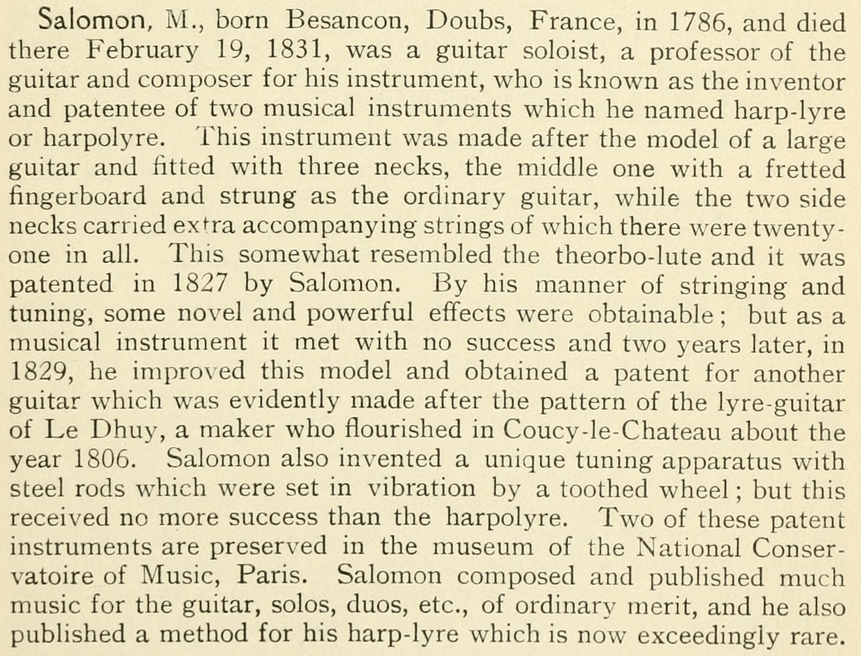

Toward the end of the piece, Gould overdubbed a second piano part to the prelude. In a Rolling Stone interview, he explained:

“The Meistersinger is not a problem because it’s so contrapuntal that it plays itself, although I must say it’s the only place where I’m going to have to cheat, because I’m going to have to put earphones on for the last three minutes, for the place where he brings back all the themes, and you have to play it four hands. It’s a piece that I’ve played just as a party piece all my life, and you can get through the first seven minutes fine, and then you say, “OK, which themes are we leaving out tonight?” — there’s just no way. So I will do it as an overdub.”

It was certainly possible to feature a guest artist to play that second part. But Gould did it himself anyways. In a way, it makes sense – why involve another pianist for just 3 minutes of music? What if Gould wanted to play this live? Would the other pianist just sit there and wait? And maybe this was not meant to be performed live? And sure, it’s fun to play with others, but you know yourself best (or, do we really know ourselves?) and it was a good chance to carry our an entire concept all on your own.

It’s quite easy to “make music with yourself” today, with a loop pedal or an app. But back then, why would artists go to studio and record a full album all by themselves? For maximum control? Because it was a novel idea and not many have done that? It’s a challenge to play with oneself? An opportunity to reflect different sides of the artist?

I don’t have an answer (what do I have answers for?). And different people do the same thing for different reasons. I do hope to make an album all by myself in the future. I will let you know how it feels when the album is finished. But until then, I would like to share a few older recordings I know of that are studio productions, with artists performing with themselves.

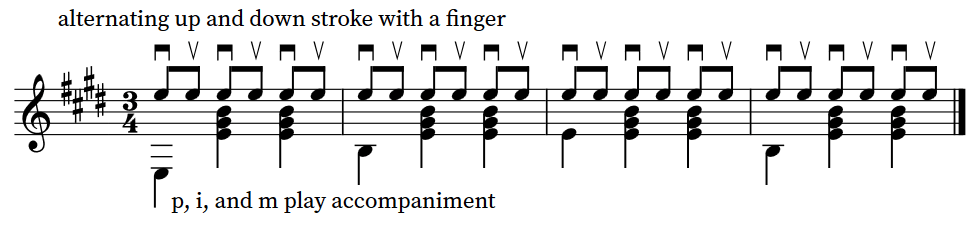

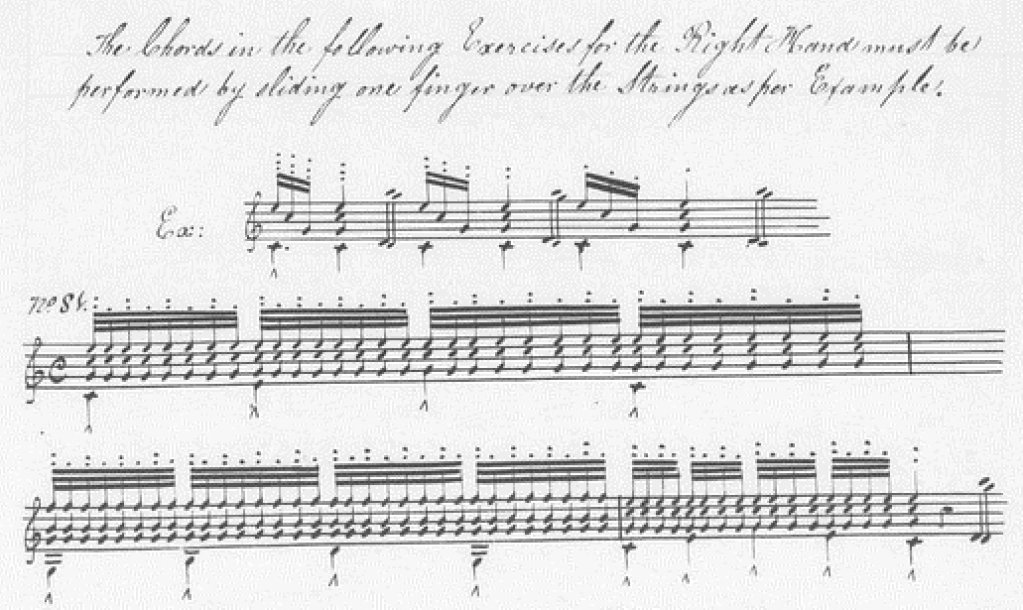

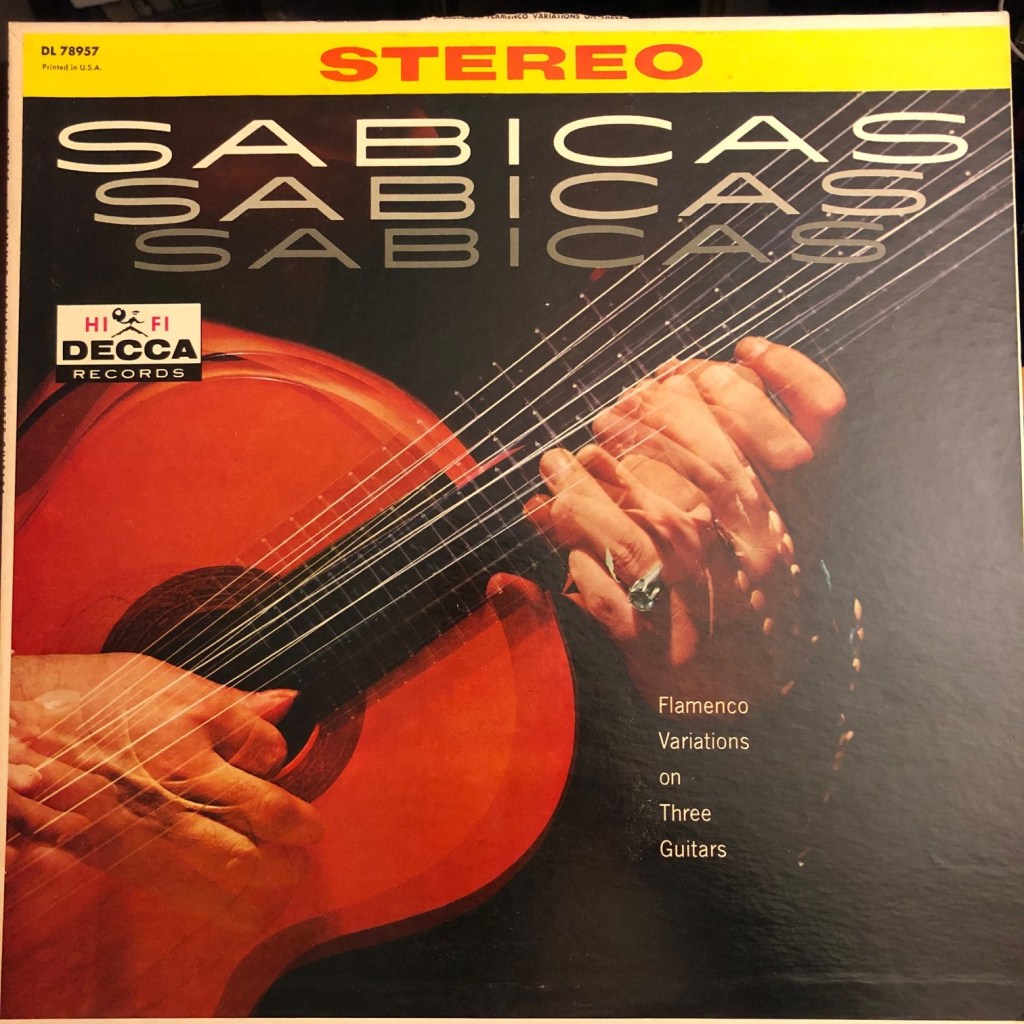

Sabicas – Flamenco Variations on Three Guitars from 1960. The album cover is pretty clever, right? An album review from the April 1960 issue of Billboard says the following:

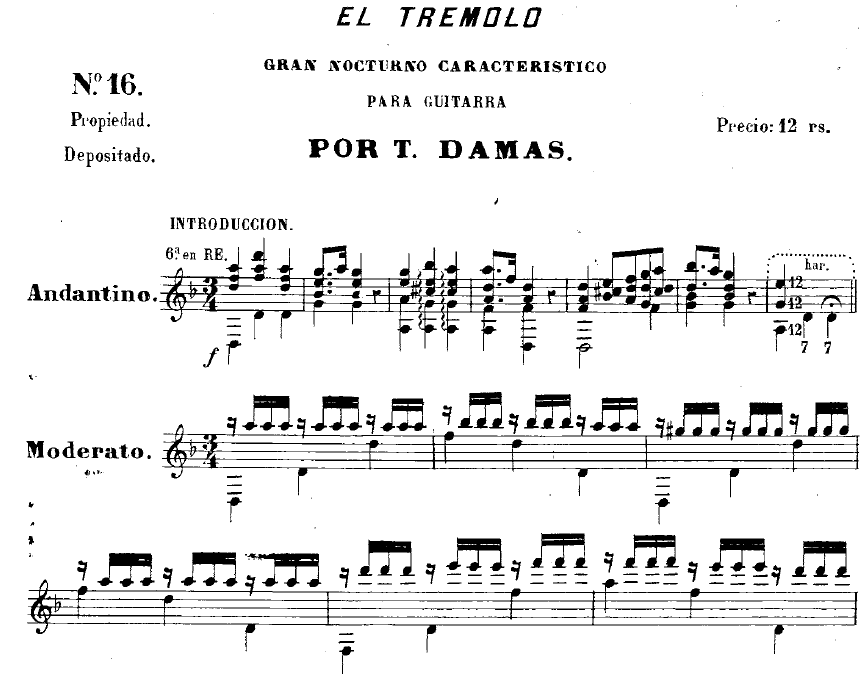

Should flamenco be categorized as folk…? If not, what should it be labelled as? Should music be categorized? I went to far… Let’s just say, three guitars playing tremolo sounds amazing, and it is great to see it was a guitarist who made a trio recording with himself?

(See the April 1960 issue of Billboard here, and see another post about a few things I found interesting from the same issue here.)

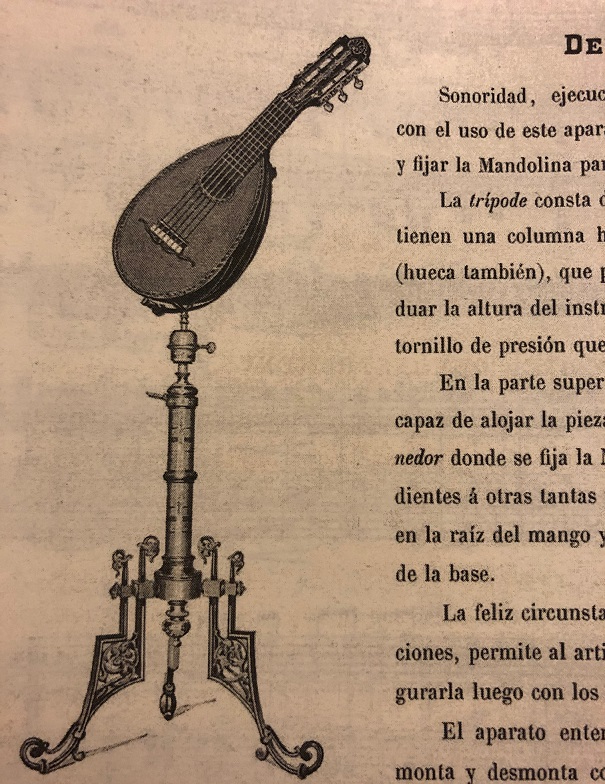

And allow me to digress – the solo guitar album Ole, La Mano!, by Juan Serrano:

I just find it funny that these two flamenco albums have the same color scheme and overlay image… The Sabicas album was released by Decca, and the Serrano released by Elektra. Was there a consensus for flamenco album covers?

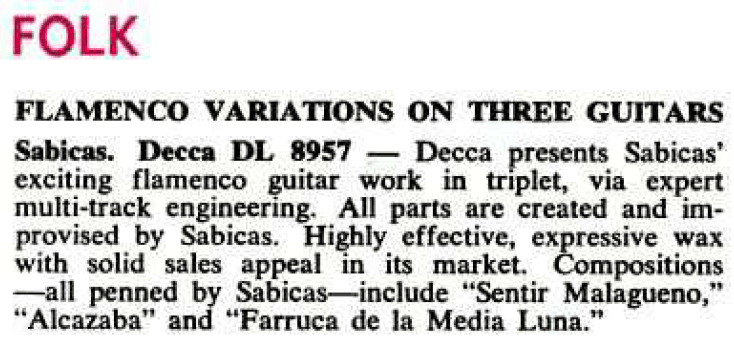

After the Sabicas “trio” album, Conversations with Myself by Bill Evans from 1963 “followed”:

Like the Sabicas album, this is also a “trio” album, with Evans overdubbing two tracks over himself. Sure… while you were in the studio, why not? Evans would later release two more albums with self-overdubs: Further Conversations with Myself (1967) and New Conversations (1978).

Another guitar album came in 1966: Music for Two Guitars/Music for One Guitar by Rey de la Torre (released by Epic Records):

My friend Anthony LaLena told me about this album. I was so glad to know yet another “all-by-myself” album made by a guitarist. This album has a very long descriptive (but not very poetic) title, because one side 1 of the album contains three duet pieces, and side 2 has the solo pieces. Must Spanish guitar albums all share the same color scheme and “repetition” aesthetics for their covers?

The aforementioned Wagner arrangement by Glenn Gould came from the 1973 album Glenn Gould Plays His Own Transcriptions of Wagner Orchestral Showpieces:

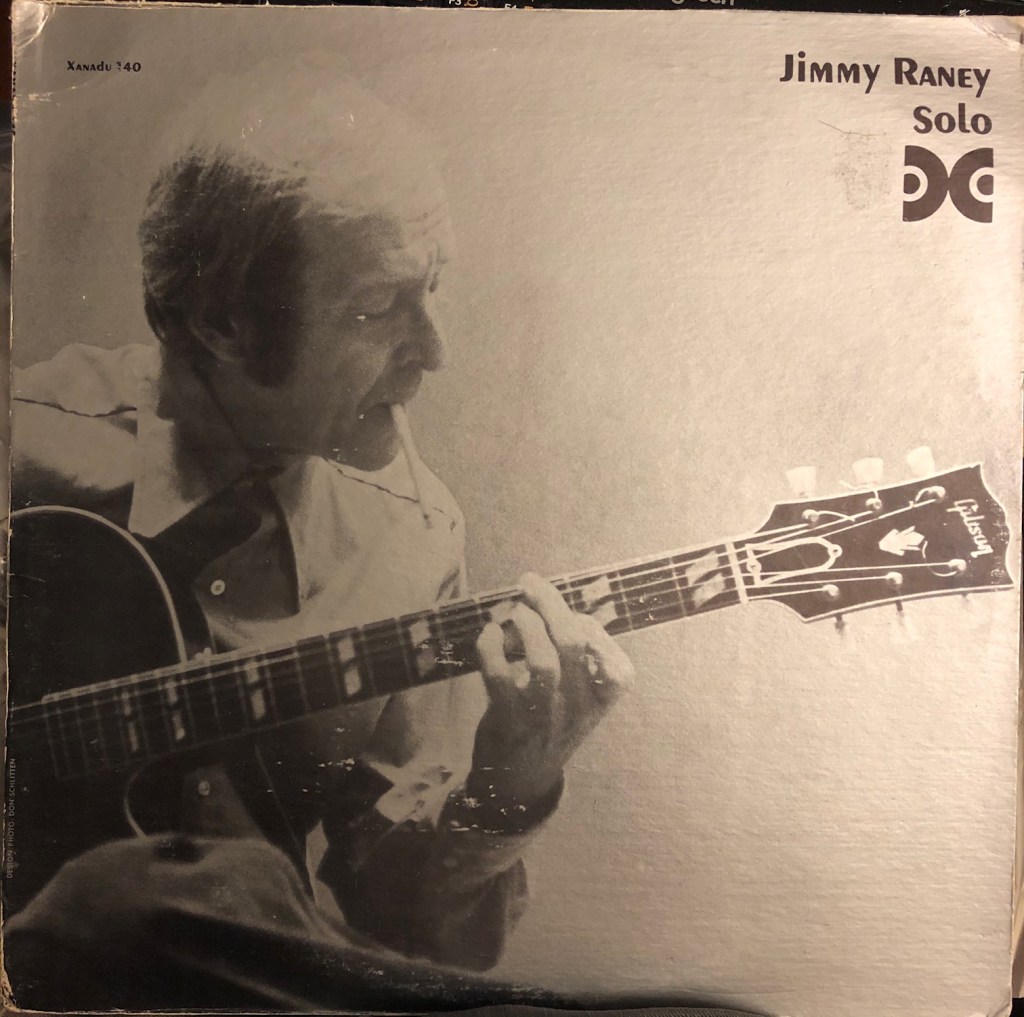

Jimmy Raney album, Solo, from 1976 is the last “self-duo” album I would like to mention:

This album has the best title…! The back cover explains the rationale:

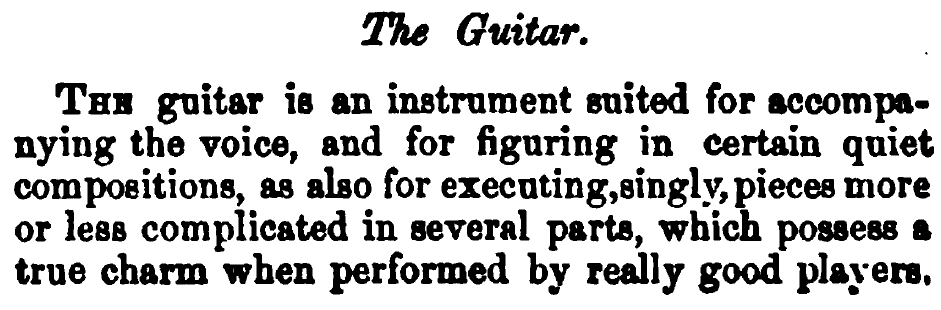

Bonus: this one is not really a full recording. It’s a video of Julian Bream (RIP) playing Luigi Boccherini’s Fandango with himself. Musicality aside, it is very dramatic – two Breams in suits of contrasting colors, throwing dirty looks at each other, as if they were in a competition, trading licks and trying to out play their opponents. The footage comes from the documentary, ¡Guitarra! from 1985.