Recently, a few people told me they have stumbled upon my website, so I thought, maybe the site is due for a little update.

Back in May 2022, the Classical Mandolin Society of America reached out to the Rochester Mandolin Orchestra, and see if the RMO would be interested in hosting the annual convention. We were a young group back then, but we ended up accepting the challenge and agreed to host the convention in 2024. Coinciding with a serendipitous encounter of an old picture of a mandolin orchestra from Rochester, I started looking into the history of mandolin in Rochester, and ended up writing two articles for the CMSA Journal. I thoroughly enjoyed learning about the different generations of mandolin orchestras since 1880s: with Fred B. Crittenden and M.E. Wolff (with annual performances at the Lyceum Theatre), Arabella Krug, Don Santos, and the Ukrainian Mandolin Orchestra. Here is a short summary of the articles, published through WXXI Classical. And if you are interested in reading the full articles, here is a PDF with the two articles combined into one.

Through the research, I have learned about a few unique characters from the Rochester music scene before the 1930s (hopefully, a later post), as well as the history of classical guitar in Rochester (this is my current focus). This post is to supplement one piece of Rochester mandolin history I failed to mention in my articles: the story of the current rendition of the RMO.

Although I went to school to study classical guitar, I grew up playing 12 years of violin. I had a cheap mandolin before I studied guitar, as I was fascinated by the Brazilian choro. As soon as I learned the mandolin share the same tuning as the violin, I got myself a Rogue mandolin for $50 on Craigslist, and tried to learn choro songs on my own (and it wasn’t very successful). As I got more focused on guitar studies, I stopped playing the mandolin entirely. It wasn’t till I was finishing up graduate school that I picked up the mandolin and choro again. And it was a lot easier than I thought, as I had 8 to 9 years of intense training in guitar and music theory at that point – I knew how to practice, my ears and reading abilities were much better.

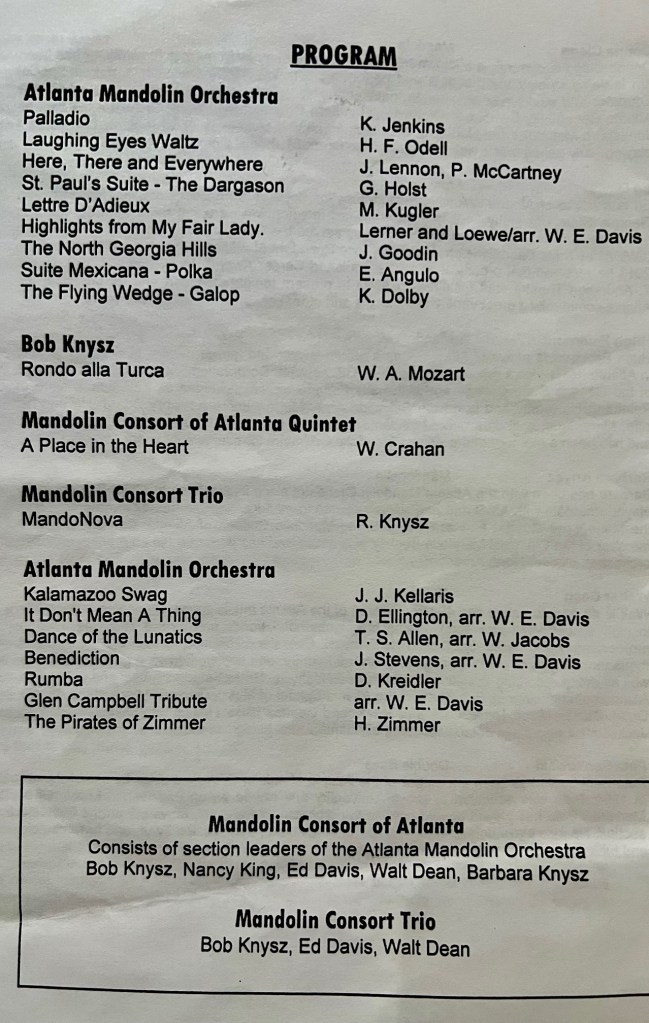

In the summer of 2018, I had a chance to teach a summer music camp in Atlanta, Georgia (which also resulted in a visit to Mississippi. This will be a later post). I was driving around one afternoon, and saw an advertisement of an upcoming concert presented by the Atlanta Mandolin Orchestra. I had experience playing in an orchestra when I was very young (until around age 11), but since becoming a classical guitarist, I hardly play with an orchestra. I was very curious, reached out to the AMO, and asked if I could sit in with them. Thinking back, this must sounded really cocky.!They accommodated my request with much generosity – they told me that it wouldn’t be easy to add a new member so close to a performance, but they offered me a free ticket to attend. The concert was very fun and the program eclectic, with performances by soloists, small groups, and full orchestras, performing music from J.S. Bach, to Duke Ellington and Antonio Carlos Jobim.

In the Fall of 2018, I was attending a concert (Muriel Anderson…?), and a friend from the Rochester Guitar Club, Tom Napoli, shared that he was interested in putting a mandolin group together. In February 2019, we began hosting a monthly meeting at Bernunzio Uptown Music on Saturday afternoons. John the owner is an avid supporter of local music, and often shared stories about his mandolin lessons with Veda Santos, long time music teacher and wife of the virtuoso, music teacher, and publisher Don Santos. Without hesitation, John added us to his rosters of workshops and jams every Saturday. The meetings at Berninzio’s were open sessions for anyone to join, and we sent out sheet music in advance for people to practice. The world stopped in March 2020, but as the summer came around, a few of the session attendees expressed interests in playing outdoors with social distancing. We met through the summer of 2020 in Tom’s backyard, and that small dedicated group of 8 or so people became the backbone of the Rochester Mandolin Orchestra.