Tremolo on classical guitar is a special technique. It creates a “continuous” sound by repeating a particular right hand fingering pattern:

thumb (p) -> ring finger (a) -> middle finger (m) -> index finger (i).

The thumb arpeggiates notes in the bass register, and the other three fingers repeat on the same note. Recuerdos de la Alhambra (composed in 1896) by Francisco Tarrega (dedicated to Alfred Cottin) is probably the most famous tremolo piece.

I had a discussion once with my teacher Nicholas Goluses about which was the first tremolo guitar piece. He thought Reverie, Op. 19 by Giulio Regondi might be the first one. With some free time on my hand now, I have given this topic another thought. There is a Classical Guitar Delcamp thread on this very topic and provided me with a great starting place. But after much digging around (on the internet), there is still no definite answer, and everything I discuss below are speculations. At least this put my brain in “thinking mode” for a good few days…

Since Tarrega composed Recuerdos de la Alhambra in 1896, and guitar methods after him (such as those by Pascual Roch and Emlio Pujol) contain exercises that drill the p-a-m-i pattern, my goal is to find a tremolo piece prior to 1896.

What is a “tremolo piece”? To me, a tremolo piece should have the following features:

1) an entire piece of music (e.g. Tarrega’s Alhambra), or a piece of music that has (a) devoted section(s) (e.g. Regondi’s Reverie) that utilize the repeating right hand p-a-m-i pattern. Using the tremolo technique intermittently does not count;

2) a “1 + 3” tremolo pattern, in which the thumb plays a bass note, follow by the a, m, i finger playing three repeated notes in a higher register. This would exclude “sextuplet” tremolo, such as those found in Fernando Sor’s Grand Solo (first published 1810);

3) the thumb notes should form an arpeggiation that outlines the underlying harmonies of the music.

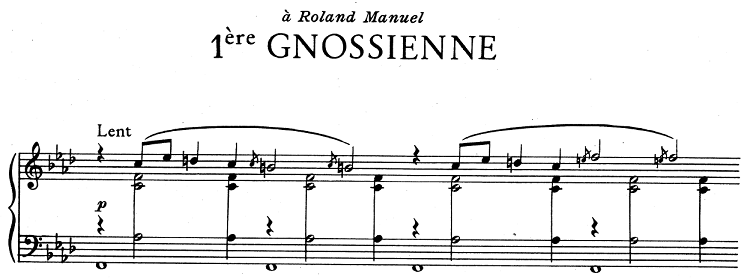

Therefore, a piece such as Etude #7 from Carcassi’s op. 60 (first published 1836) would not be a tremolo piece, since measure 2 and 3 would break the p-a-m-i pattern. The “tremolo-looking” pattern of measure 1 occurs only sporadically throughout the etude.

One thing to consider is the usage of right hand fingers in the early to mid 19th century guitar tradition: many guitarists (Sor, Carulli, Carcassi) would play mostly with p, i, and m (makes perfect sense for the Carcassi etude above), and only use the a finger for “chords and arpeggios which contain four, five or six notes” (see the introduction to Carcassi’s Op.60, written by Brian Jeffery). I don’t consider tremolo as a type of arpeggio (although Dr. Goluses did suggest me to conceive of the tremolo as a weird p-a-m-i arpeggiation). When I think of “19th century arpeggios”, the generic patterns come to mind – p-i-m-a, p-a-m-i, and other iterations. Each of the right hand finger would be resposible for playing one string, instead of having a, m, i plucking the same string.

Even though I don’t think of the tremolo as an arpeggio, it seems wrong to not check if the 120 arpeggio studies from Mauro Giuliani’s op.1 (first published 1812) would provide any insights. Sure enough, there are two “tremolo” exercises: Ex. 100 is very close to what I definied as tremolo above, except the right hand arpeggio pattern – a repeating pattern of p-a-m-i-p-i-m-a instead of just p-a-m-i. Ex. 110 does not involve the ring finger at all, conforming to the typical way of playing guitar in the 19th century with only p, i, and m.

But did Giuliani employ “tremolo” in his actual compositions? With much shame, I have to admit I don’t know all of Giuliani’s works. I just quickly check his “big” pieces – Grand Overture, 6 Rossinianas, and 3 Concerti. Two excerpts from Rossiniana #6 reveal the two ways Giuliani employed “tremolo” in his works, both of which don’t fit my definition mentioned earlier: the “sextuplet tremolo” is not a “1+3” pattern and doesn’t use the ring finger, and when a “1+3” pattern is employed, the bass is merely playing the same note an octave lower than the 3 repeated notes that follow. The bass is not forming an arpeggiation that outlines the underlying harmonies.

Some of the early 19th century guitarists also played with a pinky (lightly) anchored on the top of the guitar, which limits the movement of the ring finger. That does seem to make p-a-m-i pattern a technique of a later generation.

In his Treatise on Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration (1844), Berlioz mentioned “reiterated notes, two, three, four, and even six or eight times repeated, are easily done; prolonged reiterations (roulements) on the same note are rarely good excepting on the first string, or at the utmost on the three high strings.” He then provided us with the right hand tremolo fingering: p-i-m-i.

Was there a particular tremolo piece Berlioz had in mind?

The Classical Guitar Delcamp thread also mentioned the usage of tremolo in Mertz’s Potpourri on Verdi’s Ernami (op.8, #14). The musical features do fit the criteria of tremolo defined above – a substantial section that consistently uses a “1+3” pattern, with bass notes arpeggiating the underlying harmonic changes. But Mertz’s method (published 1848) suggests the tremolo to be played with the pattern p-m-i-m:

I checked a few more 19th century guitar methods and didactic works that came to mind: Napoleon Coste edition of Sor’s method (published 1851) and his 25 etudes (published 1873), Luigi Legnani’s method (published 1849), Madame Sidney Pratten’s Guitar School (published 1881) – all of them seem to not have included any p-a-m-i pattern exercises or music.

So I go back to Reverie by Regondi – is it the first tremolo piece? I don’t know. It fits all my criteria of being a tremolo piece, but of all the scores I could find online, none of them included any right hand fingering. And Regondi left us with a Rudimenti del Concertina, a New Method for the Concertina, and the “Golden Exercises“, but not a guitar method.

And then I stumble upon one source, which presented many more questions to be answered…

(to be continued on First Tremolo Piece For Classical Guitar #2)